This tiny print serves no purpose, but to make this book seem like an actual book. In printed books, one usually sees a large block of tiny print on the first or second page followed by terms like © 2013. All Rights Reserved. So and so. Printed in the United States of America. The publisher may also include prose to deter would-be pirates. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. That is typically followed by a line or two about the publisher, followed by a sequence of numbers.

For more information, please contact JasperCollins Publishers, 99 St Marks Pl New York, NY 94105.

12 13 14 15 16 LP/SSRH 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

But seriously, all you need to know is that this work is shared under a Creative Commons BY-NC license, which means that you can freely share and adapt it for non-commercial use with attribution.

Art direction: Ali Almossawi, Illustration: Alejandro Giraldo.

“I love this illustrated book of bad arguments.

A flawless compendium of flaws.”

“A wonderfully digestible summary of the pitfalls and techniques of argumentation. I can't think of a better way to be taught or reintroduced to these fundamental notions of logical discourse. A delightful little book.”

This book is aimed at newcomers to the field of logical reasoning, particularly those who, to borrow a phrase from Pascal, are so made that they understand best through visuals. I have selected a small set of common errors in reasoning and visualized them using memorable illustrations that are supplemented with lots of examples. The hope is that the reader will learn from these pages some of the most common pitfalls in arguments and be able to identify and avoid them in practice.

The literature on logic and logical fallacies is wide and exhaustive. This work's novelty is in its use of illustrations to describe a small set of common errors in reasoning that plague a lot of our present discourse.

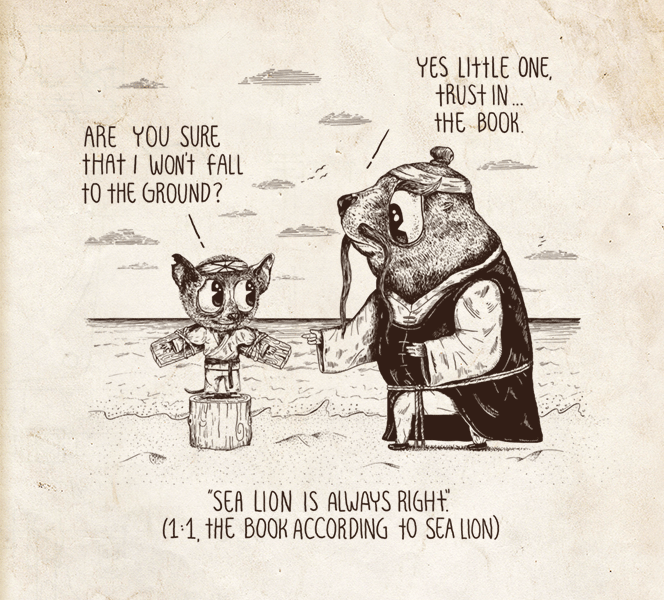

The illustrations are partly inspired by allegories such as Orwell's Animal Farm and partly by the humorous nonsense of works such as Lewis Carroll's stories and poems. Unlike such works, there isn't a narrative that ties them together; they are discrete scenes, connected only through style and theme, which better affords adaptability and reuse. Each fallacy has just one page of exposition, and so the terseness of the prose is intentional.

Reading about things that one should not do is actually a useful learning experience. In his book, On Writing, Stephen King writes: “One learns most clearly what not to do by reading bad prose.” He describes his experience of reading a particularly terrible novel as, “the literary equivalent of a smallpox vaccination” [King]. The mathematician George Pólya is quoted as having said in a lecture on teaching the subject that in addition to understanding it well, one must also know how to misunderstand it [Pólya]. This work primarily talks about things that one should not do in arguments.1

* * * *

1 For a look at the converse, see T. Edward Damer's book on faulty reasoning.

Many years ago, I spent part of my time writing software specifications using first-order predicate logic. It was an intriguing way of reasoning about invariants using discrete mathematics rather than the usual notation—English. It brought precision where there was potential ambiguity and rigor where there was some hand-waving.

During the same time, I perused a few books on propositional logic, both modern and medieval, one of which was Robert Gula's A Handbook of Logical Fallacies. Gula's book reminded me of a list of heuristics that I had scribbled down in a notebook a decade ago about how to argue; they were the result of several years of arguing with strangers in online forums and had things like, “try not to make general claims about things without evidence.” That is obvious to me now, but to a schoolboy, it was an exciting realization.

It quickly became evident that formalizing one's reasoning could lead to useful benefits such as clarity of thought and expression, objectivity and greater confidence. The ability to analyze arguments also helped provide a yardstick for knowing when to withdraw from discussions that would most likely be futile.

Issues and events that affect our lives and the societies we live, such as civil liberties and presidential elections, usually cause people to debate policies and beliefs. By observing some of that discourse, one gets the feeling that a noticeable amount of it suffers from the

absence of good reasoning. The aim of some of the writing on logic is to help one realize the tools and paradigms that afford good reasoning and hence lead to more constructive debates.

Since persuasion is a function of not only logic, but other things as well, it is helpful to be cognizant of those things. Rhetoric likely tops the list, and precepts such as the principle of parsimony come to mind, as do concepts such as the “burden of proof” and where it lies. The interested reader may wish to refer to the wide literature on the topic.

In closing, the rules of logic are not laws of the natural world nor do they constitute all of human reasoning. As Marvin Minsky asserts, ordinary common sense reasoning is difficult to explain in terms of logical principles, as are analogies, adding, “Logic no more explains how we think than grammar explains how we speak” [Minsky]. Logic does not generate new truths, but allows one to verify the consistency and coherence of existing chains of thought. It is precisely for that reason that it proves an effective tool for the analysis and communication of ideas and arguments.

– A. A., San Francisco, July 2013

The first principle is that you must not fool yourself and you are the easiest person to fool.

—Richard P. Feynman

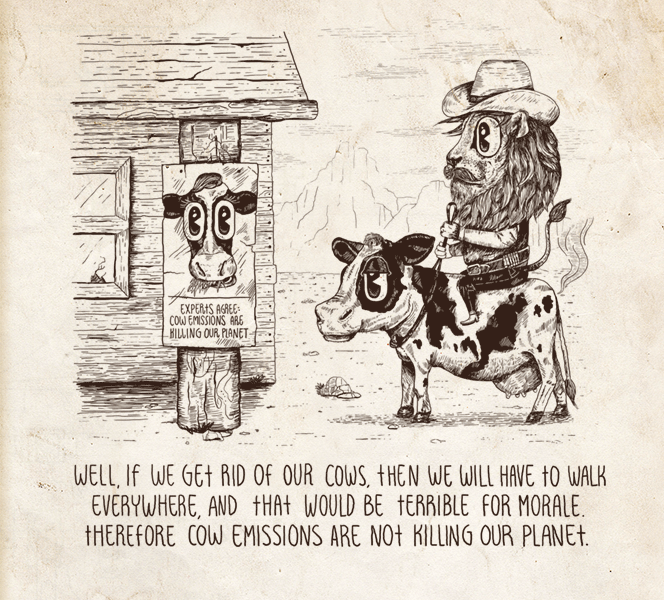

Arguing from consequences is speaking for or against the truth of a statement by appealing to the consequences of accepting or rejecting it. Just because a proposition leads to some unfavorable result does not mean that it is false. Similarly, just because a proposition has good consequences does not all of a sudden make it true. As David Hackett Fischer puts it, “it does not follow, that a quality which attaches to an effect is transferable to the cause.”

In the case of good consequences, an argument may appeal to an audience's hopes, which at times take the form of wishful thinking. In the case of bad consequences, such an argument may instead appeal to an audience's fears. For example, take Dostoevsky's line, “If God does not exist, then everything is permitted.” Discussions of objective morality aside, the appeal to the apparent grim consequences of a purely materialistic world says nothing about whether or not the antecedent is true.

One should keep in mind that such arguments are fallacious only when they deal with propositions with objective truth values, and not when they deal with decisions or policies [Curtis], such as a politician opposing the raising of taxes for fear that it will adversely impact the lives of constituents, for example.

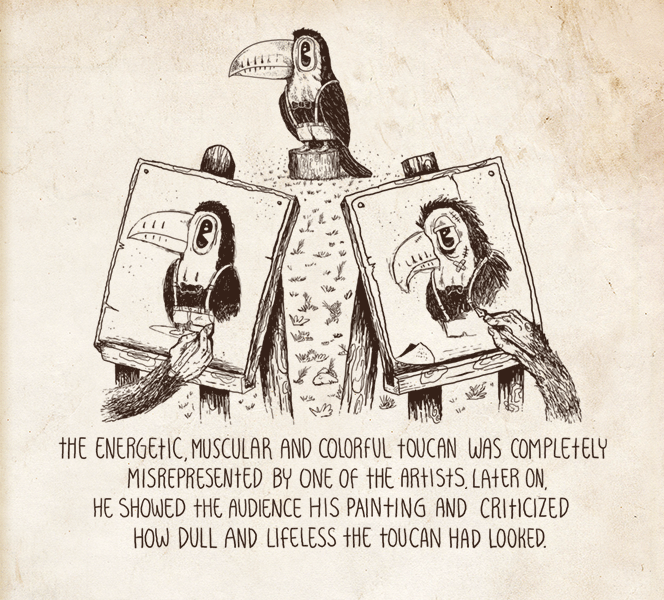

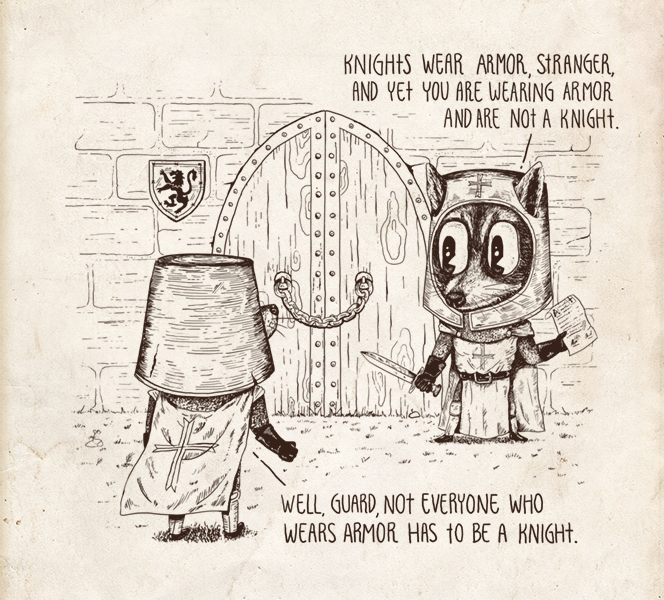

Intentionally caricaturing a person's argument with the aim of attacking the caricature rather than the actual argument is what is meant by “putting up a straw man.” Misrepresenting, misquoting, misconstruing and oversimplifying are all means by which one commits this fallacy. A straw man argument is usually one that is more absurd than the actual argument, making it an easier target to attack and possibly luring a person towards defending the more ridiculous argument rather than the original one.

For example, My opponent is trying to convince you that we evolved from monkeys who were swinging from trees; a truly ludicrous claim. This is clearly a misrepresentation of what evolutionary biology claims, which is the idea that humans and chimpanzees shared a common ancestor several million years ago. Misrepresenting the idea is much easier than refuting the evidence for it.

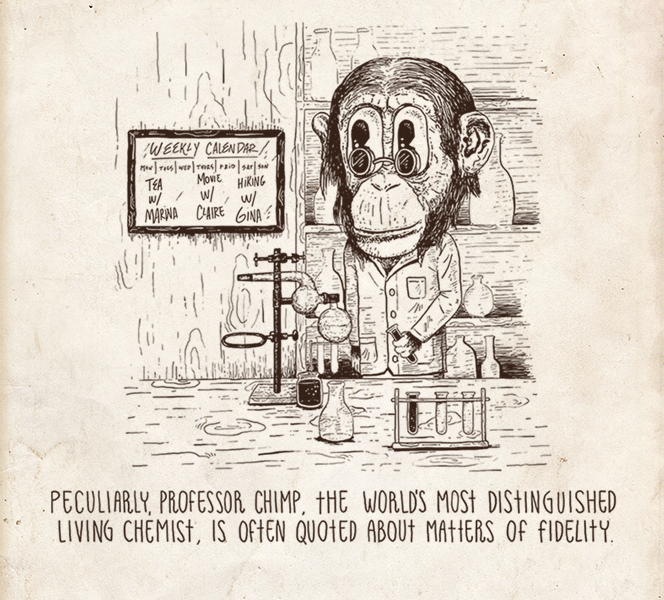

An appeal to authority is an appeal to one's sense of modesty [Engel], which is to say, an appeal to the feeling that others are more knowledgeable. While this is a comfortable and natural tendency for humans, such appeals cannot tell us which things are true and which are false. All appeals to authority are a type of genetic fallacy. Experts do not have the characteristic of producing absolute truth. To determine truth from untruth we must rely on evidence and reason.

However, appeals to relevant authority can tell us which things are likely to be true. This is the means by which we form beliefs. The overwhelming majority of the things that we believe in, such as atoms and the solar system, are on reliable authority, as are all historical statements, to paraphrase C. S. Lewis.

It is fallacious to form a belief when the appeal is to an authority who is not an expert on the issue at hand. A similar appeal worth noting is the appeal to vague authority, where an idea is attributed to a vague collective. For example, Professors in Germany showed such and such to be true. Another type of appeal to irrelevant authority is the appeal to ancient wisdom, where something is assumed to be true just because it was believed to be true some time ago. For example, Astrology was practiced by technologically advanced civilizations such as the Ancient Chinese. Therefore, it must be true. One might also appeal to ancient wisdom to support things that are idiosyncratic, or that may change with time. Such appeals need to weigh the evidence that is available to us in the present.

Equivocation exploits the ambiguity of language by changing the meaning of a word during the course of an argument and using the different meanings to support some conclusion. A word whose meaning is maintained throughout an argument is described as being used univocally. Consider the following argument: How can you be against faith when we take leaps of faith all the time, with friends and potential spouses and investments? Here, the meaning of the word “faith” is shifted from a spiritual belief in a creator to a risky undertaking.

A common invocation of this fallacy happens in discussions of science and religion, where the word “why” may be used in equivocal ways. In one context, it may be used as a word that seeks cause, which as it happens is the main driver of science, and in another it may be used as a word that seeks purpose and deals with morals and gaps, which science may well not have answers to. For example, one may argue: Science cannot tell us why things happen. Why do we exist? Why be moral? Thus, we need some other source to tell us why things happen.

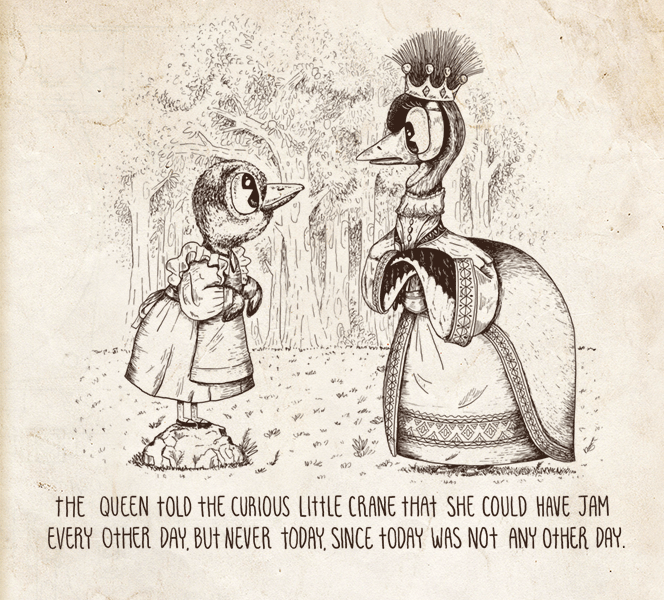

2 The illustration is based on an exchange between Alice and the White Queen in Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking-Glass.

A false dilemma is an argument that presents a set of two possible categories and assumes that everything in the scope of that which is being discussed must be an element of that set. If one of those categories is rejected, then one has to accept the other. For example, In the war on fanaticism, there are no sidelines; you are either with us or with the fanatics. In reality, there is a third option, one could very well be neutral; and a fourth option, one may be against both; and even a fifth option, one may empathize with elements of both.

In The Strangest Man, it is mentioned that physicist Ernest Rutherford once told his colleague Niels Bohr a parable about a man who bought a parrot from a store only to return it because it didn't talk. After several such visits, the store manager eventually says: “Oh, that's right! You wanted a parrot that talks. Please forgive me. I gave you the parrot that thinks.” Now clearly, Rutherford was using the parable to illustrate the genius of the silent Dirac, though one can imagine how someone might use such a line of reasoning to suggest that a person is either silent and a thinker or talkative and an imbecile.

3 This fallacy may also be referred to as the fallacy of the excluded middle, the black and white fallacy or a false dichotomy.

The fallacy assumes a cause for an event where there is no evidence that one exists. Two events may occur one after the other or together because they are correlated, by accident or due to some other unknown event; one cannot conclude that they are causally connected without evidence. The recent earthquake was due to people disobeying the king is not a good argument.

The fallacy has two specific types: ‘after this, therefore because of this’ and ‘with this, therefore because of this.’ With the former, because an event precedes another, it is said to have caused it. With the latter, because an event happens at the same time as another, it is said to have caused it. In various disciplines, this is referred to as confusing correlation with causation.4

Here is an example paraphrased from comedian Stewart Lee: I can't say that because in 1976 I did a drawing of a robot and then Star Wars came out, then they must have copied the idea from me. Here is another one that I recently saw in an online forum: The attacker took down the railway company's website and when I checked the schedule of arriving trains, what do you know, they were all delayed! What the poster failed to realize is that those trains rarely arrive on time, and so without any kind of scientific control, the inference is unfounded.

4 As it turns out, eating chocolate and winning a Nobel Prize have been shown to be highly correlated, perhaps raising the hopes of many a chocolate eater.

The fallacy plays on the fears of an audience by imagining a scary future that would be of their making if some proposition were accepted. Rather than provide evidence to show that a conclusion follows from a set of premisses, which may provide a legitimate cause for fear, such arguments rely on rhetoric, threats or outright lies. For example, I ask all employees to vote for my chosen candidate in the upcoming elections. If the other candidate wins, he will raise taxes and many of you will lose your jobs.

Here is another example, drawn from the novel, The Trial: You should give me all your valuables before the police get here. They will end up putting them in the storeroom and things tend to get lost in the storeroom. Here, although the argument is more likely a threat, albeit a subtle one, an attempt is made at reasoning. Blatant threats or orders that do not attempt to provide evidence should not be confused with this fallacy, even if they exploit one's sense of fear [Engel].

An appeal to fear may proceed to describe a set of terrifying events that would occur as a result of accepting a proposition, which has no clear causal links, making it reminiscent of a slippery slope. It may also provide one and only one alternative to the proposition being attacked, that of the attacker, in which case it would be reminiscent of a false dilemma.

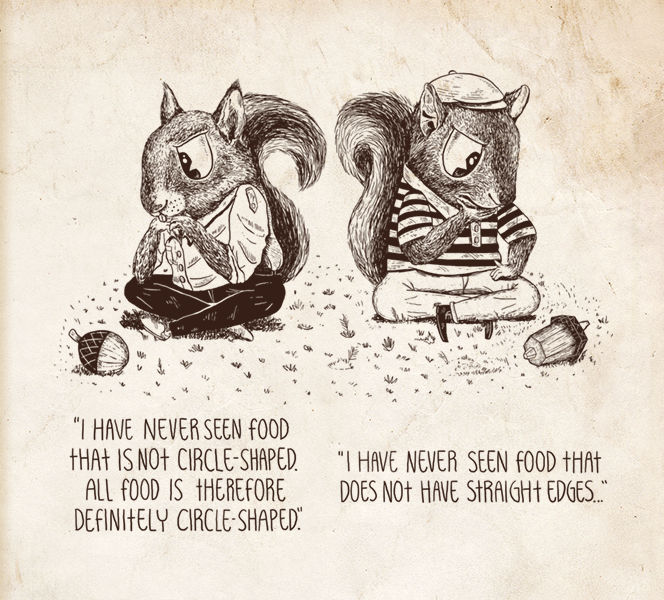

This fallacy is committed when one generalizes from a sample that is either too small or too special to be representative of a population. For example, asking ten people on the street what they think of the president's plan to reduce the deficit can in no way be said to represent the sentiment of the entire nation.

Although convenient, hasty generalizations can lead to costly and catastrophic results. For instance, it may be argued that the engineering assumptions that led to the explosion of the Ariane 5 during its first launch were the result of a hasty generalization: the set of test cases that were used for the Ariane 4 controller were not broad enough to cover the necessary set of use-cases in the Ariane 5's controller. Signing off on such decisions typically comes down to engineers' and managers' ability to argue, hence the relevance of this and similar examples to our discussion of logical fallacies.

Here is another example from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland where Alice infers that since she is floating in a body of water, a railway station, and hence help, must be close by: “Alice had been to the seaside once in her life, and had come to the general conclusion, that wherever you go to on the English coast you find a number of bathing machines in the sea, some children digging in the sand with wooden spades, then a row of lodging houses, and behind them a railway station.” [Carroll]

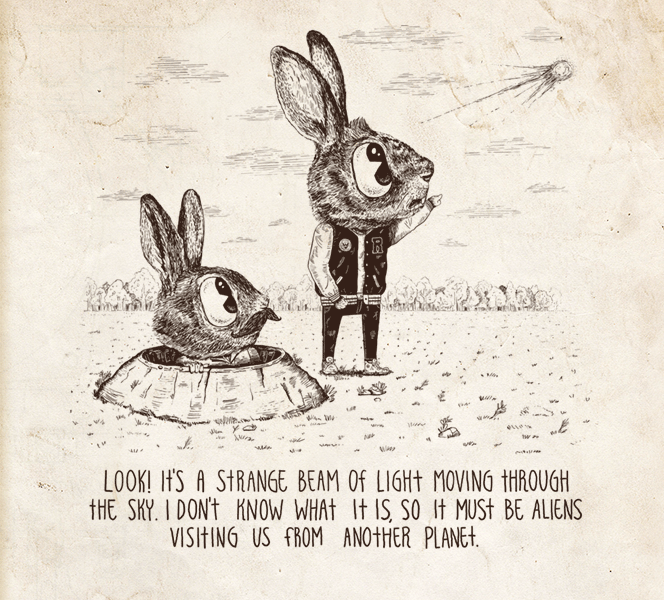

Such an argument assumes a proposition to be true simply because there is no evidence proving that it is not. Hence, absence of evidence is taken to mean evidence of absence. An example, due to Carl Sagan: “There is no compelling evidence that UFOs are not visiting the Earth; therefore UFOs exist.” Similarly, when we did not know how the pyramids were built, some concluded that, unless proven otherwise, they must have therefore been built by a supernatural power. The burden-of-proof always lies with the person making a claim.

Moreover, and as several others have put it, one must ask what is more likely and what is less likely based on evidence from past observations. Is it more likely that an object flying through space is a man-made artifact or a natural phenomenon, or is it more likely that it is aliens visiting from another planet? Since we have frequently observed the former and never the latter, it is therefore more reasonable to conclude that UFOs are unlikely to be aliens visiting from outer space.

A specific form of the appeal to ignorance is the argument from personal incredulity, where a person's inability to imagine something leads to a belief that the argument being presented is false. For example, It is impossible to imagine that we actually landed a man on the moon, therefore it never happened. Responses of this sort are sometimes wittily countered with, That's why you're not a physicist.

5 The illustration is inspired by Neil deGrasse Tyson's response to an audience member's question on UFOs: youtu.be/NSJElZwEI8o.

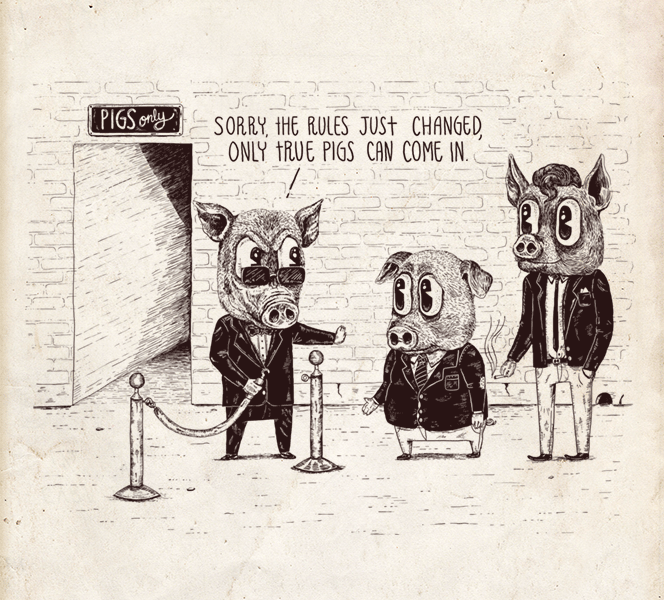

A general claim may sometimes be made about a category of things. When faced with evidence challenging that claim, rather than accepting or rejecting the evidence, such an argument counters the challenge by arbitrarily redefining the criteria for membership into that category.6

For example, one may posit that programmers are creatures with no social skills. If someone comes along and repudiates that claim by saying, “But John is a programmer, and he is not socially awkward at all”, it may provoke the response, “Yes, but John isn't a true programmer.” Here, it is not clear what the attributes of a programmer are, nor is the category of programmers as clearly defined as the category of, say, people with blue eyes. The ambiguity allows the stubborn mind to redefine things at will.

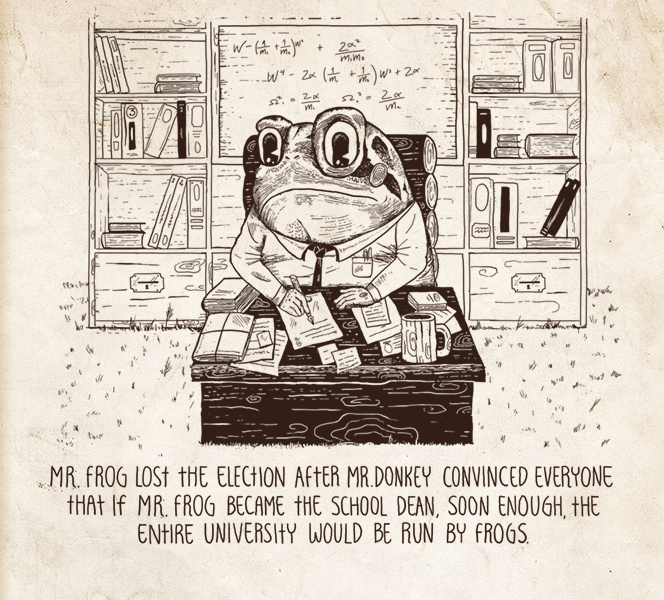

The fallacy was coined by Antony Flew in his book Thinking about Thinking. There, he gives the following example: Hamish is reading the newspaper and comes across a story about an Englishman who has committed a heinous crime, to which he reacts by saying, “No Scotsman would do such a thing.” The next day, he comes across a story about a Scotsman who has committed an even worse crime; instead of amending his claim about Scotsmen, he reacts by saying, “No true Scotsman would do such a thing.”

6 When an attacker maliciously redefines a category, knowing well that by doing so, he or she is intentionally misrepresenting it, the attack becomes reminiscent of the straw man fallacy.

An argument's origins or the origins of the person making it have no effect whatsoever on the argument's validity. A genetic fallacy is committed when an argument is either devalued or defended solely because of its history. As T. Edward Damer points out, when one is emotionally attached to an idea's origins, it is not always easy to disregard the former when evaluating the latter.

Consider the following argument, Of course he supports the union workers on strike; he is after all from the same village. Here, rather than evaluating the argument based on its merits, it is dismissed because the person happens to come from the same village as the protesters. That piece of information is then used to infer that the person's argument is therefore worthless. Here is another example: As men and women living in the 21st century, we cannot continue to hold these Bronze Age beliefs. Why not, one may ask. Are we to dismiss all ideas that originated in the Bronze Age simply because they came about in that time period?

Conversely, one may also invoke the genetic fallacy in a positive sense, by saying, for example, Jack's views on art cannot be contested; he comes from a long line of eminent artists. Here, the evidence used for the inference is as lacking as in the previous examples.

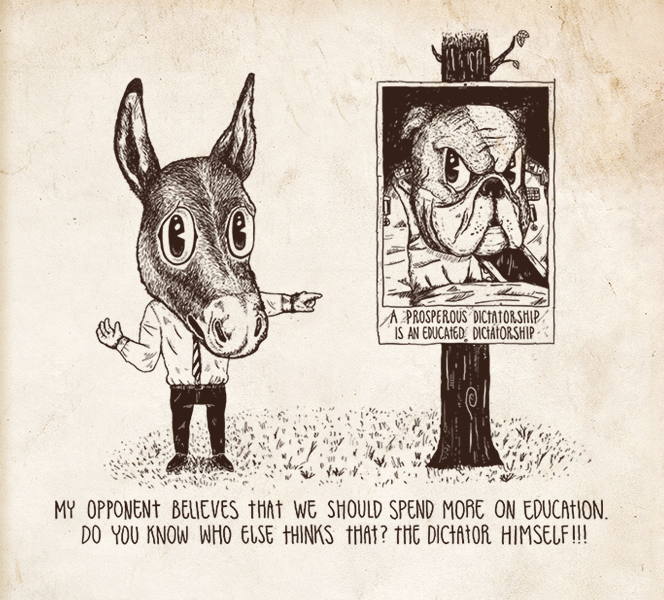

Guilt by association is discrediting an argument for proposing an idea that is shared by some socially demonized individual or group. For example, My opponent is calling for a healthcare system that would resemble that of socialist countries. Clearly, that would be unacceptable. Whether or not the proposed healthcare system resembles that of socialist countries has no bearing whatsoever on whether it is good or bad; it is a complete non sequitur.

Another type of argument, which has been repeated ad nauseam in some societies, is this: We cannot let women drive cars because people in godless countries let their women drive cars. Essentially, what this and previous examples try to argue is that some group of people is absolutely and categorically bad. Hence, sharing even a single attribute with said group would make one a member of it, which would then bestow on one all the evils associated with that group.

One of several valid forms of argument is known as modus ponens (the mode of affirming by affirming) and takes the following form: If A then C, A; hence C. More formally:

A ⇒ C, A ⊢ C.

Here, we have three propositions: two premisses and a conclusion. A is called the antecedent and C the consequent. For example, If water is boiling at sea level, then its temperature is at least 100°C. This glass of water is boiling at sea level; hence its temperature is at least 100°C. Such an argument is valid in addition to being sound.

Affirming the consequent is a formal fallacy that takes the following form:

If A then C, C; hence A.

The error it makes is in assuming that if the consequent is true, then the antecedent must also be true, which in reality need not be the case. For example, People who go to university are more successful in life. John is successful; hence he must have gone to university. Clearly, John's success could be a result of schooling, but it could also be a result of his upbringing, or perhaps his eagerness to overcome difficult circumstances. More generally, one cannot say that because schooling implies success, that if one is successful, then one must have received schooling.

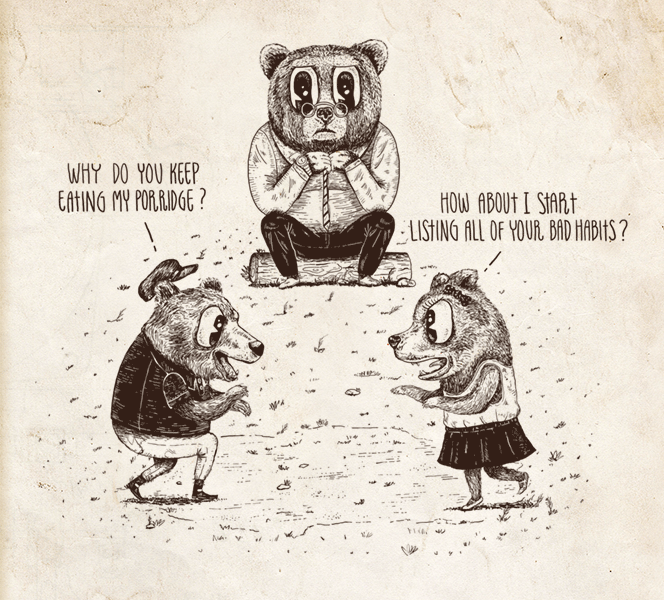

Also known by its Latin name, tu quoque, meaning you too, the fallacy involves countering a charge with a charge, rather than addressing the issue being raised, with the intention of diverting attention away from the original argument. For example, John says, “This man is wrong because he has no integrity; just ask him why he was fired from his last job,” to which Jack replies, “How about we talk about the fat bonus you took home last year despite half your company being downsized.” The appeal to hypocrisy may also be invoked when a person attacks another because what he or she is arguing for conflicts with his or her past actions [Engel].

On an episode of the topical British TV show, Have I Got News For You, a panelist objected to a protest in London against corporate greed because of the protesters' apparent hypocrisy, by pointing out that while they appear to be against capitalism, they continue to use smartphones and buy coffee. That excerpt is available here.

Here is another example from Jason Reitman's movie, Thank You for Smoking (Fox Searchlight Pictures, 2005), where a tu quoque-laden exchange is ended by the smooth-talking tobacco lobbyist Nick Naylor: “I'm just tickled by the idea of the gentleman from Vermont calling me a hypocrite when this same man, in one day, held a press conference where he called for the American tobacco fields to be slashed and burned, then he jumped on a private jet and flew down to Farm Aid where he rode a tractor onstage as he bemoaned the downfall of the American farmer.”

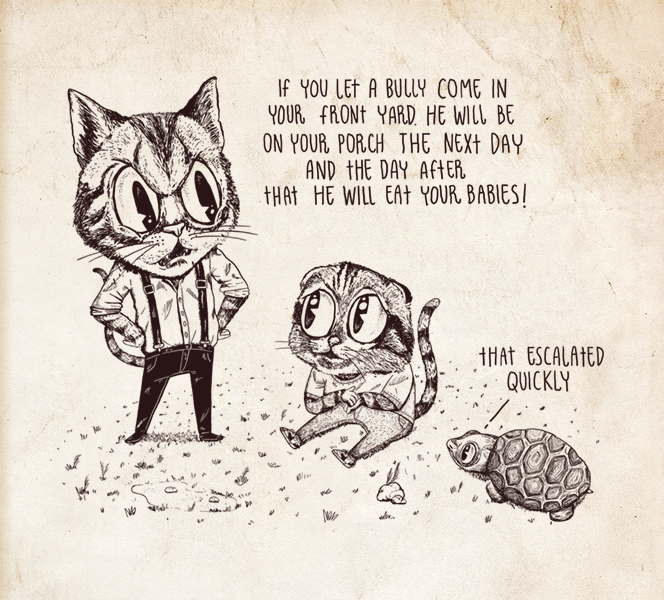

A slippery slope7 attempts to discredit a proposition by arguing that its acceptance will undoubtedly lead to a sequence of events, one or more of which are undesirable. Though it may be the case that the sequence of events may happen, each transition occurring with some probability, this type of argument assumes that all transitions are inevitable, all the while providing no evidence in support of that. The fallacy plays on the fears of an audience and is related to a number of other fallacies, such as the appeal to fear, the false dilemma and the argument from consequences.

For example, We shouldn't allow people uncontrolled access to the Internet. The next thing you know, they will be frequenting pornographic websites and, soon enough our entire moral fabric will disintegrate and we will be reduced to animals. As is glaringly clear, no evidence is given, other than unfounded conjecture, that Internet access implies the disintegration of a society's moral fabric, while also presupposing certain things about the conduct.

7 The slippery slope fallacy described here is of a causal type.

Also known as the appeal to the people, such an argument uses the fact that a sizable number of people, or perhaps even a majority, believe in something as evidence that it must therefore be true. Some of the arguments that have impeded the widespread acceptance of pioneering ideas are of this type. Galileo, for example, faced ridicule from his contemporaries for his support of the Copernican model. More recently, Barry Marshall had to take the extreme measure of dosing himself in order to convince the scientific community that peptic ulcers may be caused by the bacterium H. pylori, a hypothesis that was, initially, widely dismissed.

Luring people into accepting that which is popular is a method frequently used in advertising and politics. For example, All the cool kids use this hair gel; be one of them. Although becoming a “cool kid” is an enticing offer, it does nothing to support the imperative that one should buy the advertised product. Politicians frequently use similar rhetoric to add momentum to their campaigns and influence voters.

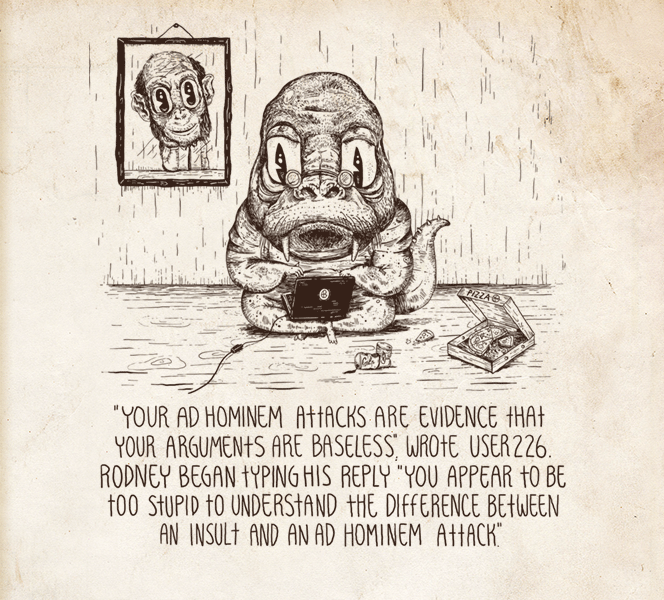

An ad hominem argument is one that attacks a person's character rather than what he or she is saying with the intention of diverting the discussion and discrediting the person's argument. For example, You're not a historian; why don't you stick to your own field. Here, whether or not the person is a historian has no impact on the merit of their argument and does nothing to strengthen the attacker's position.

This type of personal attack is referred to as abusive ad hominem. A second type, known as circumstantial ad hominem, is any argument that attacks a person for cynical reasons, by making a judgment about their intentions. For example, You don't really care about lowering crime in the city, you just want people to vote for you. There are situations where one may legitimately bring into question a person's character and integrity, such as during a testimony.

8 The illustration is inspired by a discussion on Usenet several years ago in which an overzealous and stubborn programmer was a participant.

Circular reasoning is one of four types of arguments known as begging the question, [Damer] where one implicitly or explicitly assumes the conclusion in one or more of the premisses. In circular reasoning, a conclusion is either blatantly used as a premiss, or more often, it is reworded to appear as though it is a different proposition when in fact it is not. For example, You're utterly wrong because you're not making any sense. Here, the two propositions are one and the same since being wrong and not making any sense, in this context, mean the same thing. The argument is simply stating, ‘Because of x therefore x,’ which is meaningless.

A circular argument may at times rely on unstated premisses, which can make it more difficult to detect. Here is an example from the Australian TV series, Please Like Me, where one of the characters condemns the other, a non-believer, to hell, to which he responds, “[That] doesn't make any sense. It's like a hippie threatening to punch you in your aura.” In this example, the unstated premiss is that there exists a God who sends a subset of people (non-believers) to hell. Hence, the premiss, ‘There exists a God who sends non-believers to hell’ is only supported by the evidence of the assertion that the non-believer is going to hell, which is the conclusion from, ‘There exists a God who sends non-believers to hell.’ and the attestation that the person is a non-believer.

Composition is inferring that a whole must have a particular attribute because its parts happen to have that attribute. If every sheep in a flock has a mother, it does not then follow that the flock has a mother, to paraphrase Peter Millican. Here is another example: Each module in this software system has been subjected to a set of unit tests and has passed them all. Therefore, when the modules are integrated, the software system will not violate any of the invariants verified by those unit tests. The reality is that the integration of individual parts introduces new complexities to a system due to dependencies that may in turn introduce additional avenues for potential failure.

Division, conversely, is inferring that a part must have some attribute because the whole to which it belongs happens to have that attribute. For example, Our team is unbeatable. Any of our players would be able to take on a player from any other team and outshine him. While it may be true that the team as a whole is unbeatable, one cannot use that as evidence to infer that each of its players is thus unbeatable. A team's success is clearly not always the sum of the individual skills of its players.

Many years ago, I heard a professor introduce deductive arguments using a wonderful metaphor, describing them as watertight pipes where truth goes in one end and truth comes out the other end. As it happens, that was the inspiration for this book's cover. Having reached the end of this book, I hope that you leave not only with a better appreciation of the benefits of watertight arguments in validating and expanding knowledge, but also of the complexities of inductive arguments where probabilities come into play. With such arguments in particular, critical thinking proves an indispensable tool. I hope that you also leave with a realization of the dangers of flimsy arguments and how commonplace they are in our everyday lives.

Scroll down for more · Share on Twitter Facebook

Proposition: A statement that is either true or false, but not both. For example, Boston is the largest city in Massachusetts.

Premiss: A proposition that provides support to an argument's conclusion. An argument may have one or more premisses. Also spelled premise.

Argument: A set of propositions aimed at persuading through reasoning. In an argument, a subset of propositions, called premisses, provides support for some other proposition called the conclusion.

Deductive argument: An argument in which if the premisses are true, then the conclusion must be true. The conclusion is said to follow with logical necessity from the premisses. For example, All men are mortal. Socrates is a man. Therefore, Socrates is mortal. A deductive argument is intended to be valid, but of course might not be.

Inductive argument: An argument in which if the premisses are true, then it is probable that the conclusion will also be true.9 The conclusion therefore does not follow with logical necessity from the premisses, but rather with probability. For example, Every time we measure the speed of light in a vacuum, it is 3 × 108 m/s. Therefore, the speed of light in a vacuum is a universal constant. Inductive arguments usually proceed from specific instances to the general.

9 In science, one usually proceeds inductively from data to laws to theories, hence induction is the foundation of much of science. Induction is typically taken to mean testing a proposition on a sample, either because it would be impractical or impossible to do otherwise.

Logical fallacy: An error in reasoning that results in an invalid argument. Errors are strictly to do with the reasoning used to transition from one proposition to the next, rather than with the facts. Put differently, an invalid argument for an issue does not necessarily mean that the issue is unreasonable. Logical fallacies are violations of one or more of the principles that make a good argument such as good structure, consistency, clarity, order, relevance and completeness.

Formal fallacy: A logical fallacy whose form does not conform to the grammar and rules of inference of a logical calculus. The argument's validity can be determined just by analyzing its abstract structure without needing to evaluate its content.

Informal fallacy: A logical fallacy that is due to its content and context rather than its form. The error in reasoning ought to be a commonly invoked one for the argument to be considered an informal fallacy.

Validity: A deductive argument is valid if its conclusion logically follows from its premisses. Otherwise, it is said to be invalid. The descriptors valid and invalid apply only to arguments and not to propositions.

Soundness: A deductive argument is sound if it is valid and its premisses are true. If either of those conditions does not hold, then the argument is unsound. Truth is determined by looking at whether the argument's premisses and conclusions are in accordance with facts in the real world.

Strength: An inductive argument is strong if in the case that its premisses are true, then it is highly probable that its conclusion is also true. Otherwise, if it is improbable that its conclusion is true, then it is said to be weak. Inductive arguments are not truth-preserving; it is never the case that a true conclusion must follow from true premisses.

Cogency: An inductive argument is cogent if it is strong and the premisses are actually true–that is, in accordance with facts. Otherwise, it is said to be uncogent.

Falsifiability: An attribute of a proposition or argument that allows it to be refuted, or disproved, through observation or experiment. For example, the proposition, All leaves are green, may be refuted by pointing to a leaf that is not green. Falsifiability is a sign of an argument's strength, rather than of its weakness.

[Aristotle] Aristotle, On Sophistical Refutations, translated by W. A. Pickard, http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/sophist_refut.html

[Avicenna] Avicenna, Treatise on Logic, translated by Farhang Zabeeh, 1971.

[Carroll] Lewis Carroll, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, 2008,

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/11/11-h/11-h.htm

[Curtis] Gary N. Curtis, Fallacy Files, http://fallacyfiles.org

[Damer] T. Edward Damer, Attacking Faulty Reasoning: A Practical Guide to Fallacy-Free Arguments (6th ed), 2005.

[Engel] S. Morris Engel, With Good Reason: An Introduction to Informal Fallacies, 1999.

[Farmelo] Graham Farmelo, The Strangest Man: The Hidden Life of Paul Dirac, Mystic of the Atom, 2011.

[Fieser] James Fieser, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, http://www.iep.utm.edu

[Firestein] Stuart Firestein, Ignorance: How it Drives Science, 2012.

Scroll down for more · Share on Twitter Facebook

[Fischer] David Hackett Fischer, Historians' Fallacies: Toward a Logic of Historical Thought, 1970.

[Gula] Robert J. Gula, Nonsense: A Handbook of Logical Fallacies, 2002.

[Hamblin] C. L. Hamblin, Fallacies, 1970.

[King] Stephen King, On Writing, 2000.

[Minsky] Marvin Minsky, The Society of Mind, 1988.

[Pólya] George Pólya, How to Solve It: A New Aspect of Mathematical Method, 2004.

[Russell] Bertrand Russell, The Problems of Philosophy, 1912,

http://ditext.com/russell/russell.html

[Sagan] Carl Sagan, The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark, 1995.

[Simanek] Donald E. Simanek, Uses and Misuses of Logic, 2002,

http://www.lhup.edu/~dsimanek/philosop/logic.htm

[Smith] Peter Smith, An Introduction to Formal Logic, 2003.

Scroll down for more · Share on Twitter Facebook

This has been An Illustrated Book of Bad Arguments. Thanks for visiting. Sightings of unintended irony should be reported to the author!

If you would like to help support this book with a donation, that would be much appreciated. Thank you! (Also, now on Substack.)

Background image courtesy of subtlepatterns